“Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening”

by the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial (NLST) Research Team

N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 4;365(5):395-409 [free full text]

—

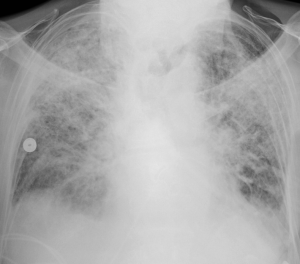

Despite a reduction in smoking rates in the United States, lung cancer remains the number one cause of cancer death in the United States as well as worldwide. Earlier studies of plain chest radiography for lung cancer screening demonstrated no benefit, and in 2002 the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) was undertaken to determine whether then recent advances in CT technology could lead to an effective lung cancer screening method.

The study enrolled adults age 55-74 with 30+ pack-years of smoking (if former smokers, they must have quit within the past 15 years). Patients were randomized to either the intervention of three annual screenings for lung cancer with low-dose CT or to the comparator/control group to receive three annual screenings for lung cancer with PA chest radiograph. The primary outcome was mortality from lung cancer. Notable secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality and the incidence of lung cancer.

53,454 patients were randomized, and both groups had similar baseline characteristics. The low-dose CT group sustained 247 deaths from lung cancer per 100,000 person-years, whereas the radiography group sustained 309 deaths per 100,000 person-years. A relative reduction in rate of death by 20.0% was seen in the CT group (95% CI 6.8 – 26.7%, p = 0.004). The number needed to screen with CT to prevent one lung cancer death was 320. There were 1877 deaths from any cause in the CT group and 2000 deaths in the radiography group, so CT screening demonstrated a risk reduction of death from any cause of 6.7% (95% CI 1.2% – 13.6%, p = 0.02). Incidence of lung cancer in the CT group was 645 per 100,000 person-years and 941 per 100,000 person-years in the radiography group (RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.03 – 1.23).

Lung cancer screening with low-dose CT scan in high-risk patients provides a significant mortality benefit. This trial was stopped early because the mortality benefit was so high. The benefit was driven by the reduction in deaths attributed to lung cancer, and when deaths from lung cancer were excluded from the overall mortality analysis, there was no significant difference among the two arms. Largely on the basis of this study, the 2013 USPSTF guidelines for lung cancer screening recommend annual low-dose CT scan in patients who meet NLST inclusion criteria. However, it must be noted that, even in the “ideal” circumstances of this trial performed at experienced centers, 96% of abnormal CT screening results in this trial were actually false positives. Of all positive results, 11% led to invasive studies.

Per UpToDate, since NSLT, there have been several European low-dose CT screening trials published. However, all but one (NELSON) appear to be underpowered to demonstrate a possible mortality reduction. Meta-analysis of all such RCTs could allow for further refinement in risk stratification, frequency of screening, and management of positive screening findings.

No randomized trial has ever demonstrated a mortality benefit of plain chest radiography for lung cancer screening. The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial tested this modality vs. “community care,” and because the PLCO trial was ongoing at the time of creation of the NSLT, the NSLT authors trial decided to compare their intervention (CT) to plain chest radiography in case the results of plain chest radiography in PLCO were positive. Ultimately, they were not.

Further Reading:

1. USPSTF Guidelines for Lung Cancer Screening (2013)

2. NLST @ ClinicalTrials.gov

3. NLST @ Wiki Journal Club

4. NLST @ 2 Minute Medicine

5. UpToDate, “Screening for lung cancer”

Summary by Duncan F. Moore, MD

Image Credit: Yale Rosen, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons